Cost per value (CPV): a new media business model

The history of media can be told in the history of its business models, which themselves depend on the time and society that spawned them.

The first step toward media measurement was in 1869, when George Rowell published The American Newspaper Directory with the circulation numbers that advertisers used to quantify their print advertising campaigns. Ads were billed per ‘insertion’ in the print run, the term ‘insertion order’ (or ‘IO’) living on even now in some media deals.

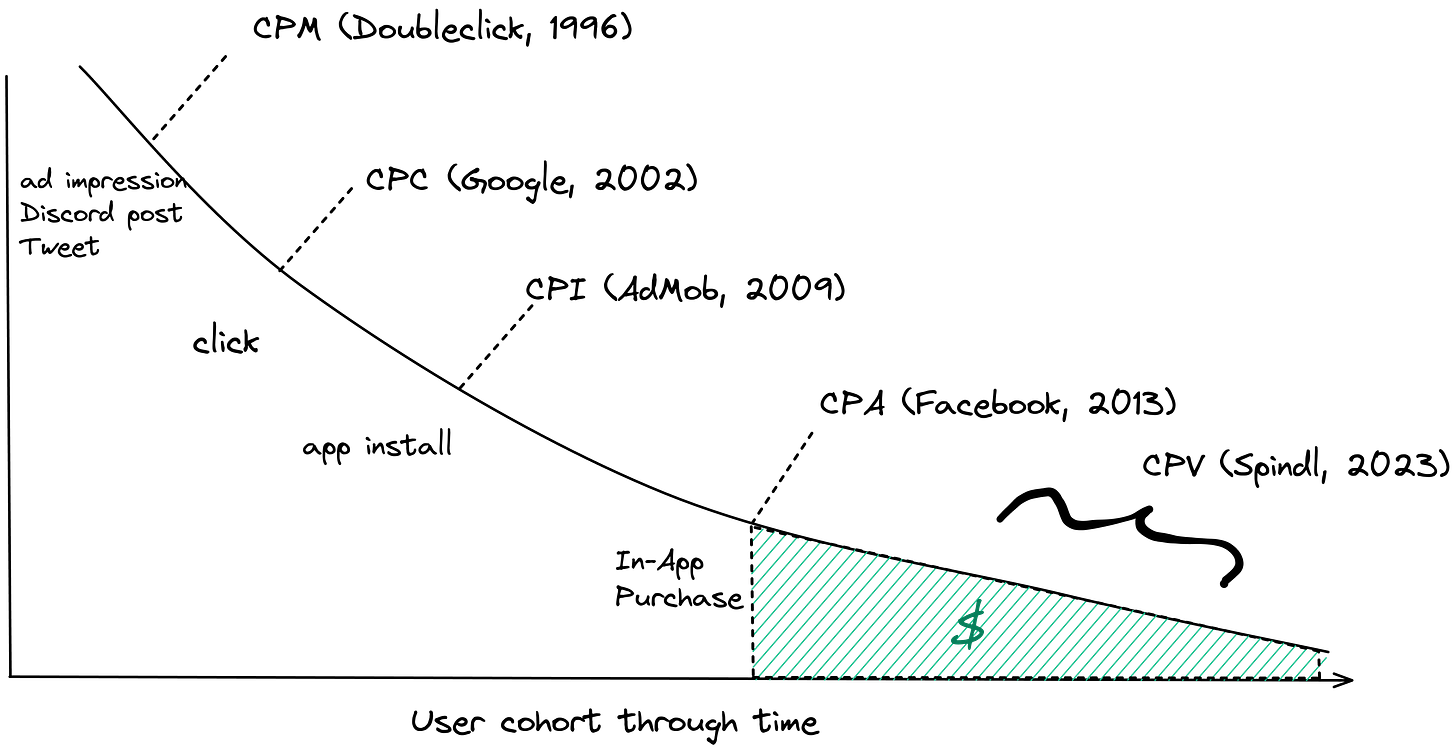

The fast-iterating Internet cycled through business models much faster than print. The first online ad ran on 1994 on a site called ‘HotWired.com’ (now WIRED Magazine), and was billed exactly like a print ad, nobody having any idea how to charge for online media. Publishers soon settled on CPM (cost per mille) as the dominant business model for more than a decade: the cost of showing an ad a thousand times on the website. There was nothing like user tracking to understand what (if anything) happened downstream of an ad: advertisers simply paid to flood certain websites with ads and hoped to God it generated sales somehow.

The first step in the direction of real performance marketing was Google adopting CPC (cost per click) as their dominant business model, only charging advertisers if a user actually clicked on an ad. A trifling-seeming change, but it precipitated a revolt among conventional marketing channels that considered themselves above any sort of performance guarantees.

In Googled, an account of the search giant’s early days, Ken Auletta recounts a hostile meeting between the Google founders and Comcast’s Mel Karmazin, a virtuoso at selling billions in unmeasurable media. “YOU’RE FUCKING WITH THE MAGIC!” an irate Karmazin yelled at the 20-something founders, who had the unhinged idea of actually measuring Google’s impact on advertiser sales.

The magic got even more fucked with when cost-per-install (CPI) ads became a thing around 2009 or so, mobile ad networks like AdMob/Google only charging advertisers if an ad actually generated an App Store install. The plumbing required to do this was the first real attribution: code runs on the app to see if an app launches for the first time, along with some click plumbing to see how they got there. This got piped back to the ads system to ring the cash register on the CPI deal: the advertiser only paid if an install happened, a model which ultimately generated billions in ad revenue for both Google and Facebook from about 2013 on.

Matters went even further with the launch of cost-per-action (CPA) ads, where advertisers were only charged if user did some arbitrary action inside the advertiser’s app: someone actually buying something or upgrading to the paid plan of an app. Advertisers loved the ability to ‘fire and forget’: just configure the attribution SDK correctly, set a bid or the action you want, and the machine more or less did the rest.

In the most flattering light, Web 2 attribution was the capital ‘T’ Truth that established causality—this tweet led to that install—in an otherwise chaotic Internet. More cynically, attribution answered the question: do I pay Google or Facebook for this user?

Web 3 attribution will be very different, both fairer and more complex.

CPA marketing is not quite the risk-free arbitrage it might seem though. Marketers still had to model their users’ lifetime value (LTV) and compare it to the acquisition cost (CAC) defined by all the CPA bids they paid. Users could still under-monetize, or the acquisition cost of the average CPA could still be unsustainably high, but it was better than the dumb old days of paying CPM for ads people ignored.

This business of charging for ads based on performance depends critically on the newfound role of ‘attribution’: an independent event-tracking system that determines where a user came from, how much revenue they generate, and who should take credit for it.

In the most flattering light, Web 2 attribution was the capital ‘T’ Truth that established causality—this Facebook ad led to that install—in an otherwise chaotic Internet. More cynically, attribution answered the question: do I pay Google or Facebook for this user (and was it worth it)? That’s all it really did in the end, and does even now.

One of Spindl’s fundamental theses is that Web 3 and blockchain technologies will represent a big step forward along the same trend line of more complex business models and greater advertiser control. Web 3 marketing will also be decentralized and more fair than Web 2 ad technology, pushing value to the real influencers, publishers, and tastemakers and skipping distribution monopolies.

How’s it all going to work?

It’s not ad tech without TLAs (three-letter acronyms), so we present CPV, or cost-per-value user acquisition.

The uniqueness of the blockchain is as a global and complete (though often hard to query) ledger of all user actions that that transferred value across the entire on-chain Internet. Rather than speedrun the Web 2 saga by paying for things like unmeasured tweets and Discord posts, why not pay a revenue-share kickback on the actual value the user generated? Why not bake the actual return on advertising spend (ROAS) into the very business model itself, and take almost all risk out of advertising for the advertiser, while also rewarding the right publishers (or even users) for their engagement?

So who gets paid with CPV?

Everyone potentially, including even the user. Rather than the attribution machinery picking a winner among Google or Facebook or AppLovin, it can weigh all the touch points—a shared link, a Discord post, an air drop, a NFT loyalty card—and consider who should share in the credit (and revenue) of the acquired user.

The on-chain part of the Spindl construct can pay an arbitrary number of players commensurate with their contribution to the resulting monetization. ‘Multi-touch attribution,’ the holy grail of marketers tired of (over)crediting this or that marketing channel, can finally be realized fully in the on-chain CPV business model. The advertiser doesn’t shell out a penny (or a token) if the user didn’t perform the target actions of interest: buying and hold the NFT, staking liquidity for 30 days or more, buying and holding a trading position, whatever.

With blockchains and smart contracts mediating the complex relationship between publisher and advertiser, parasitic Web 2-style incumbents are unnecessary for sophisticated media business models to thrive. The global namespace of wallets and the shared database of the chain, along with transparent logic like smart contracts, can be wired together to produce a decentralized version of their user-acquisition machines.

Doing this natively on the blockchain is key as, in one of Web 3’s many eccentricities, marketing budgets are typically locked up in the protocol’s native token and subject to DAO governance votes (!) of the form “should we do this user acquisition rewards program, token holders?” If you can’t pay out people on-chain, you’re not getting the marketing budget, as most Web 3 natives do not have the knee-jerk reflex to shovel fiat over to Google or Facebook for new users (thank God).

Influencers or publishers (like questing platforms, gaming guilds or wallets) can now be measured in terms of how much real value they drive. Real users can also derive rewards from real app usage, keeping them loyal in a Web 3 world that’s increasingly transactional and frictionless.

Perhaps most importantly, with blockchains and smart contracts mediating the complex relationship between publisher and advertiser, parasitic Web 2-style incumbents are unnecessary for sophisticated media business models to thrive. We don’t need a Google or Facebook to make something like CPA marketing happen; the global namespace of wallets and the shared database of the chain, along with transparent logic like smart contracts, can be wired together to produce a decentralized version. We are certainly not there yet, though you can already see inklings.

Organic growth and ‘community’ alone did not create the literal trillions in market cap of the Web 2 Internet: a hyper-efficient user-acquisition machine did. It’s time to build the same for Web 3 along fully Web 3 lines. We think CPV, or something very much like it, is its native business model and we plan to build a good chunk of it.

Join us.

Subscribe to our blog for more wild-eyed Web 3 marketing theory.

Great post with fantastic historical context.

I agree with where the marketing space is heading; a fairer revenue share with users and publishers (/networks).

It will definitely be more complex.

How do you see this working in a world with private activities and value accrual? I see that we are in a temporary phase of "everything being public" in Web3 / crypto, but we will soon move to everything being private.