Attribution rules the world

And why it'll rule Web 3 as well

This is the first post in a series on how Web 3 can mature toward a more sophisticated ecosystem. The second post is on how Web 3 can pay for itself with ads (yes, ads….but don’t recoil in horror). More posts will be forthcoming.

I consider it completely unimportant who in the party will vote, or how; but what is extraordinarily important is this — who will count the votes, and how.

-Joseph Stalin

Internet monetization is somewhat like a Soviet election: It doesn’t matter who clicks and where, it’s who counts those clicks that matters. The technology and business of that counting of clicks (and everything else you do online besides) goes by the dull-sounding name of attribution, and it determines the fate of trillion-dollar companies.

Attribution is kind of like running water and flush toilets in modern cities: Nobody but plumbers really think about it, but if it failed for you and everyone else, you would think about nothing else and civilization would teeter on the brink of the abyss.

Just what happens when attribution goes awry?

In February, the Company Formerly Known as Facebook lost a quarter (!) of its value after it admitted that Apple’s Ads Tracking and Transparency initiative (ATT) made it increasingly hard for them to actually serve ads. They projected a $10 billion-dollar hole in this year’s revenues as a result.

More recently, this week Snap lost about half its value in a massive market plunge thanks to a warning by CEO Evan Spiegel that the company would face revenue headwinds and slow hiring. The downturn was blamed on everything from supply chain issues to the war in Ukraine (!). I wasn’t aware that Snap memes came on ships from China, nor that the memes of production were located in the embattled Donbas region of Ukraine. More likely is what Eric Seufert speculates in his always-enlightening MobileDevMemo (and similar to what happened to Meta): Apple making proper attribution impossible via its privacy moves has hosed the company’s ability to drive results for its advertisers.

Let’s go even bigger picture:

Why is Twitter—our global public square where tastes are made, people canceled, and heads of state threaten each other with nuclear hellfire—worth so little a billionaire can scrape together the cash to outright buy it? How is it possible that the upstream media source to everything bought or voted on is worth a pittance compared to Google or Facebook? Attribution is why: they never take credit for all the valuable behavior they cause.

How does it work in practice?

Consider the timeline of your average internet user as they traverse the pixelated world of smartphones and desktop computers: An initial Tweet or TikTok video leads to a click, which leads to the user installing an app, which eventually leads to spending money inside an app, possibly days or weeks later. The central metaphor of marketing is the user ‘funnel’: the narrowing procession of users that get closer and closer to your cash register as they navigate the noisy internet world. I depict it here horizontally, as a cohort going down a slippery slope:

The green dollar sign is how you get paid; the red dollar sign is you paying (either directly for ads, or indirectly for organic media like tweets). The ratio of those numbers defines whether you live or die in the pixel jungle. It also determines how much (or how little) you spend on any given piece of media, cf. Facebook’s latest problems with performance.

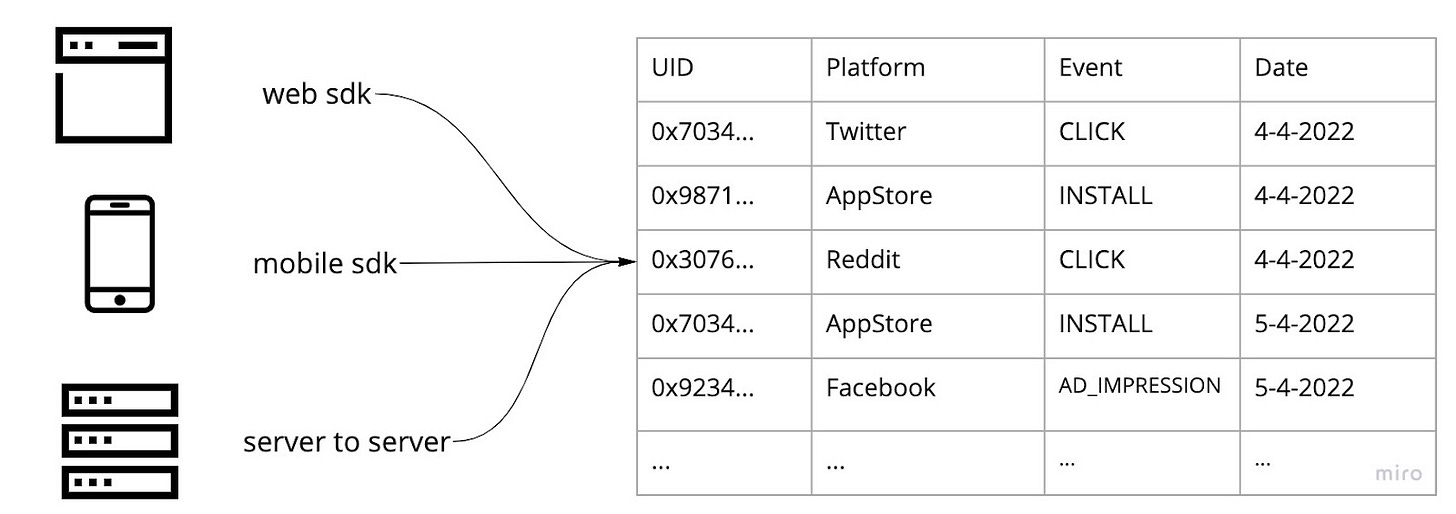

Plumbing-wise, this works because everything you touch online—every app, every website—fires events back to companies like Facebook or Branch describing what happened when, and by whom (anonymized of course). This is the source of the perennial panic about apps (e.g., period tracking ones) sending data supposedly to Facebook and divulging your personal info. It’s really not as nefarious as it sounds, and not terribly different than the server logs littered with our information we leave everywhere we go online. I’ve simplified this severely here, but it looks something like this:

I’ve removed lots of columns, but the key thing is you have an anonymous user ID as well as types and sources for various user actions. This is a huge firehose of data, easily millions of records a second all the live-long day, that needs to be stored at fairly massive expense. Then comes the actual work involved:

As we see on the right most record, someone came and dropped $10 in our app. So how’d they get there?

Even with all this tracking of users on every device, the human experience of the internet firehose is convoluted: You listen to a Rogan episode where he mentions a product, you see an ad for it in your Instagram, and then you Google search to find the product and click on the resulting Google ad. What caused you to actually buy that thing? That’s the real work of attribution, and it’s a gnarly phenomenological problem, even now in Web 2.

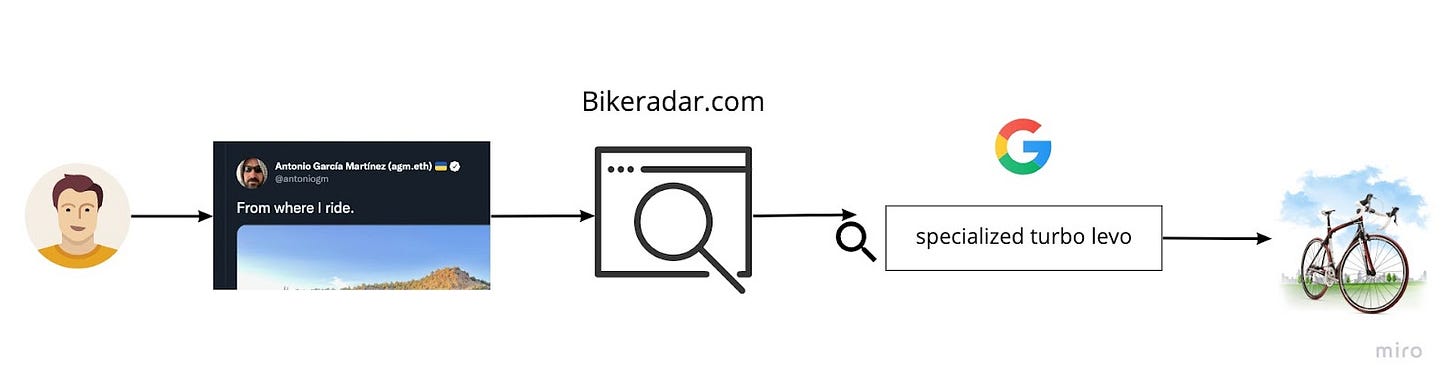

A recent example of questionable attribution: I tweeted about my e-mountain bike, Jason Calacanis (of all people) saw it and asked about the model. Someone posted a review from bikeradar.com, and Jason (I don’t know if this is true) probably googled for it and maybe bought it. Who deserves the attributions credit? According to Google (surprise, surprise), it’ll be Google … and they’ll take all the credit, which is why Google is worth so much and Twitter so little.

As with most things online, the right solution is too hard to implement, so instead everyone uses the dumbest one possible: Whoever last touched the user gets the credit. This is part of what underwrites Google’s trillion-dollar market cap: the ability to claim that everyone who bought something via a Google search bought that thing because of Google. Reality is of course much more complicated—people often use Google navigationally to lazily find some website—and Google is essentially stealing credit (and everybody in ad tech knows this).

Flawed though it is, without attribution you’re living in an acausal world of chaos, with no ability to discern related events stemming from a single human. With attribution, the endless reams of inbound clicks and page-loads that an app publisher sees—that’s all of us wildly clicking on our black mirrors all day—can be threaded together into a logical story. Whether it be circulation numbers for 19th-century newspapers (the start of the printed ads business), or Nielsen ratings for pre-cable TV that determined ads rates there, there’s never been a media ecosystem that didn’t have attribution. Which is why I feel confident in saying that Web 3 will certainly have some version of that great virtual cash register, ringing every time a user drops real (or crypto) coin.

Correct attribution in Web3 isn’t some horrible intrusion of skeumorphic Web 2 machinery, it’s a way to correctly credit a digital asset (and ultimately its owner) with the revenue they produced, in whatever downstream form. It’s the causal link that joins a human interacting with virtual goods and the very real revenue they eventually generate. Without it, the NFT market will struggle to be more than a speculative art market mimicking the real-world one. Nothing wrong with that, but here’s a whole other world of art, media, and human experience to underwrite in Web 3, and which won’t exist without the messy but necessary machinery of attribution and eventually (gasp!) ads.

Web 2 types often criticize the blockchain as an intractable and weird architecture, unsuited to most consumer Internet applications. If you think about it though, the one piece of core Web 2 infrastructure where the blockchain is actually the most natural way to engineer things is … attribution.

For their part, Web 2 types often criticize the blockchain as an intractable and weird architecture, unsuited to most consumer Internet applications. If you think about it though, the one piece of core Web 2 infrastructure where the blockchain is actually the most natural way to engineer things is … attribution. What else is a company like Branch Metrics (my former employer) or the internal attribution system at giants like Facebook, but a large, distributed, semi-private ledger of online events and data shared among various players, none of whom trust each other? If you had to conjure some collective mechanism for storing aggregated data that was selectively shareable between publisher and advertiser, it would look much like a blockchain.

I’m dubious that much else of Web 2 will survive the hop to Web 3, either from the tech or consumer point of view. The one thing I’m absolutely convinced will have to exist for Web 3 to succeed is effective and natively on-chain attribution that gives NFTs and other virtual goods their due (and gets their owners paid). In the next post in this series, I’ll look at what the marketing world will look like in a fully Web 3 world. As for the question of whether Web 3 will have ads … well, it already does.

Your continuing ability to be astonishingly insightful is really amazing.

Spindl's vision for web3 is one that does not protect user privacy. They condemn Apple's "ask not to track" -- but user's want this level of control over their own data. The author compares attribution to critical infrastructure like plumbing that if failed civilization "would teeter on the brink of the abyss." Then he cites Meta and Snap losing revenue as an example of civilization teetering on the brink of abyss. Web3 should give users what they want and Spindl is working against this.